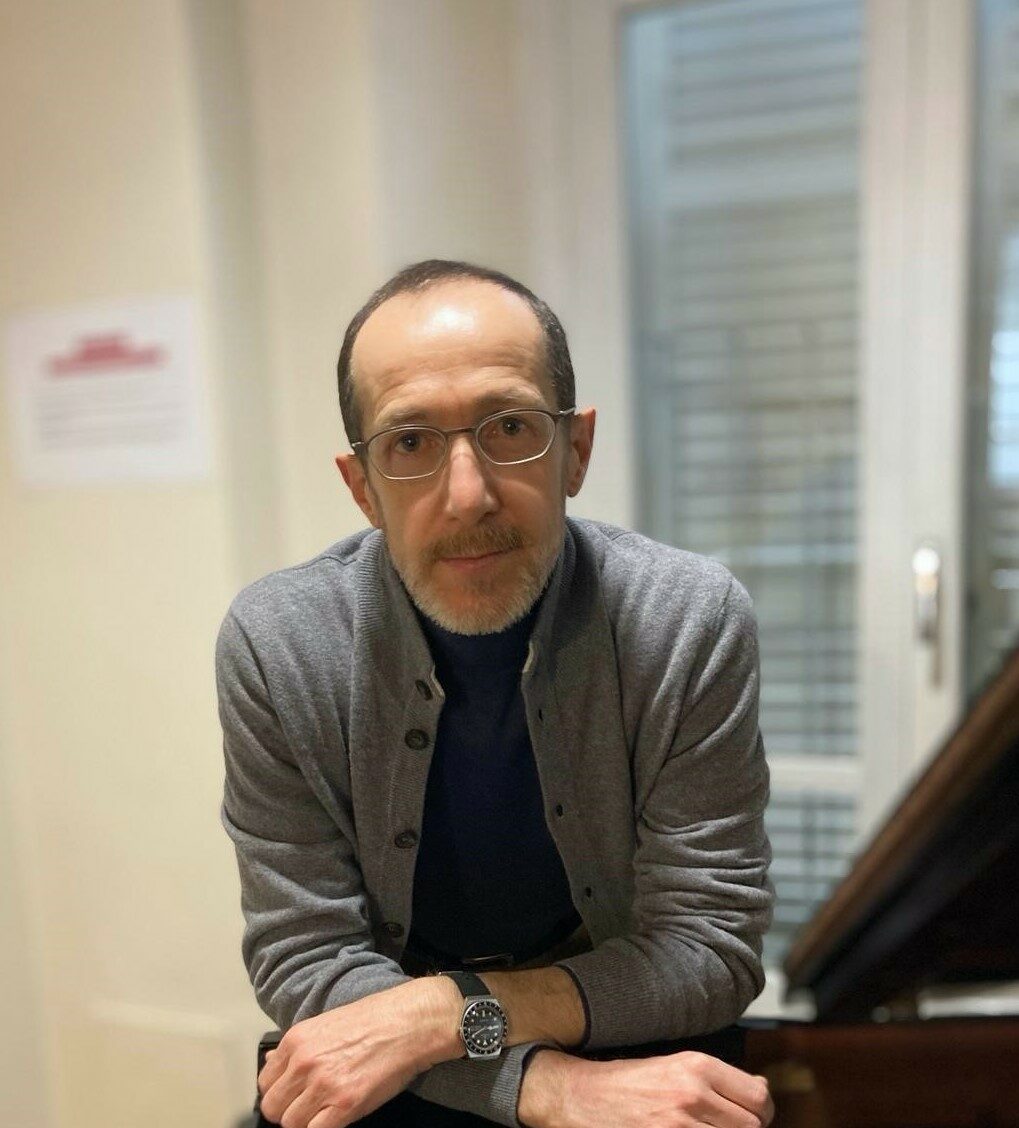

Pictures at an Exhibition is probably Mussorgsky’s most popular work, though he never had the satisfaction of knowing that. Plagued by severe depression, the composer basically drank himself to an early death at age 42, leaving many works unrevised for publication.

Like many other of Mussorgsky’s works, Pictures was subjected to the hubris of other composers, who sought to clean up and correct what they perceived as mistakes or carelessness on Mussorgsky’s part, but were in actuality his strikingly original and “willfully eccentric” language (Dannreuther, The Oxford History of Music). Even though Mussorgsky’s friend Rimsky-Korsakov was well-meaning, he still was not faithful to the original manuscript when he prepared it for publication in 1886. It wasn’t until 1931 that Pictures was published as it was truly written.

Today we’re more familiar with Ravel’s brilliant orchestration of the work than as a solo piano suite. It was not immediately popular to pianists, perhaps because the goliath Mussorgsky had a ridiculously large reach and did not write awesome passagework for us average sized plebes.

What is so fascinating about Pictures at an Exhibition was that the work is not merely a musical description of the artwork, but Mussorgsky’s own emotional experience as a viewer and his eventual integration into the scenes of the exhibition. This is done brilliantly through his use of promenades, which link the ten movements and represent the composer himself walking from painting to painting in various emotional states. Mussorgsky remarked that these interludes depict him “roving through the exhibition, now leisurely, now briskly in order to come close to a picture that had attracted his attention, and at times sadly, thinking of his departed friend” (Artist and architect Viktor Hartmann died suddenly of an aneurysm in 1873, at the young age of 39, and Mussorgsky had been devastated at the loss. He poured his feelings into letters to his friend, critic Vladimir Stasov, who had organized the Hartmann exhibition, and to whom Pictures was dedicated to).

Mussorgsky admitted in his letters that the grandiosity in which he wrote the promenade themes reflect his own elephantine body. I’m hoping that he said that jokingly. I’m imagining the blimp-like composer stomping around the gallery, oblivious to the tiny people scattering out of his way as his moved.

This “promenade theme” feels like a Russian folksong, with strong simple rhythms, but its constant switching to asymmetrical meters depict cleverly the hesitating pace of an art-lover at a gallery. His individual perception of each painting is represented by the fact that each movement is built from the musical motives of the promenade theme. The distinction between observer and observed fall away with the 2nd half of the piece, as the Mussorgsky descends into the Catacombs with Hartmann and the promenades disappear.

But I’ve blabbed enough for today, and will save next week will be a more detailed exploration into the 11 paintings that inspired the suite, as well its the orchestration history in the 20th century.

Selected movements from Pictures at an Exhibition will be performed on October 9th, on the first Sunday Social of the year. The suite in its entirety will be performed on the Art and Music concert, which takes place Saturday, October 15th. Click here to reserve your tickets!