When you first arrive at Garth Newel, you are embraced by an enchanting spirit that you sense must arise from a rich history. What is the story of the place itself, and who were the people who built it? Who has lived and worked on this beautiful century-old estate on the slope of Warm Springs Mountain … and who turned it into such an amazing music center in rural western Virginia? The story is a remarkable one, a saga of scandal, wealth, love of the arts, and extraordinary vision and persistence—which all led to the Garth Newel Music Center we know today.

Garth Newel cherishes its roots. Each Memorial Day Weekend, it honors its founders with three days of concerts, fine dining, and great company. This year, on Saturday evening, May 24, founders Luca and Arlene Di Cecco (who recently celebrated their 65th wedding anniversary), will be present to share in the celebration. By the way, seats are selling fast, so if you plan on coming, so it’s a good idea to buy your tickets soon.

The Di Ceccos not only established Garth Newel Music Center in 1973 along with Christine Herter Kendall—they performed in the original chamber music ensemble, taught students, provided amazing food, and transformed an idea into the thriving and well-respected music center that now draws audiences from near and far. They shepherded Garth Newel through its first quarter of a century, establishing its commitment to professional live chamber music, music education, fine cuisine, nurturing creativity, and warm hospitality. Their vision for Garth Newel has energized the mission ever since.

New Beginnings: A Scandal and a New Home

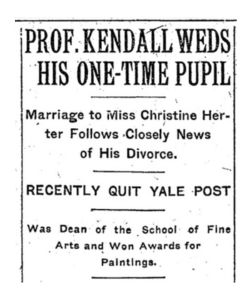

The story of Garth Newel begins about fifty years before the Di Ceccos entered the picture, when respected artist William Sergeant Kendall divorced his wife and married his much-younger student Christine Herter—at 32, she was 21 years his junior. Scandal erupted—on the pages of the New York Times—as Kendall resigned as dean of fine arts at Yale. The newlyweds escaped the uproar by fleeing to Bath County. That may seem an unlikely choice, but Hot Springs had long been a favored retreat for the wealthy of New York City.

The story of Garth Newel begins about fifty years before the Di Ceccos entered the picture, when respected artist William Sergeant Kendall divorced his wife and married his much-younger student Christine Herter—at 32, she was 21 years his junior. Scandal erupted—on the pages of the New York Times—as Kendall resigned as dean of fine arts at Yale. The newlyweds escaped the uproar by fleeing to Bath County. That may seem an unlikely choice, but Hot Springs had long been a favored retreat for the wealthy of New York City.

They purchased a 114-acre lot on the western slope of Warm Springs Mountain and set about creating a new home for themselves. They named it “Garth Newel,” which means “new home” in Welsh.

The Kendalls’ residence, which we know as the Manor House but they called “the Big House,” has an unusual design for American architecture at the time. Reminiscent of some of the great houses of England, the home has a large hall at the center of the first floor, perfect for social gatherings such as chamber music evenings. In addition, there were art studios; one of them, with high ceilings and loads of natural light, was in what has become the Stradivarius Suite. Christine’s artwork can still be seen hanging in several places in the Manor House.

William and Christine were both amateur violinists, and they enjoyed hosting music evenings in their home. As Christine’s family had done when she was growing up, the couple enjoyed hosting music evenings in their home. In addition to performing themselves, they also hosted professional musicians. As The New York Times reported on November 29, 1931, “Mr. and Mrs. William Sergeant Kendall were hosts to more than seventy-five members of the colony at Garth Newell this afternoon at a musicale and tea, presenting the Brosa String Quartet of London.”

Both Kendalls loved horses and were avid riders. They built state-of-the-art stables [link to blog article] for their prize-winning Andalusians. There was also an indoor riding ring, quite elegant compared to the norm. In fact, that’s where concerts are now held, after the transformed space was named Herter Hall in Christine’s memory.

In 1938, unfortunately, William died from a riding accident. By 1954, Christine no longer wanted to live in the “Big House” by herself, so she built a smaller modernist house, designed by noted North Carolina architect James Walter Fitzgibbon, a bit down the hill. Now called Kendall House, it has served as the residence for Garth Newel’s executive directors through the years.

Christine lived on the property until she died in 1981, but she didn’t want the amazing property to stagnate. She wanted the estate to serve a larger purpose and be of use to more people. She donated it to the Girl Scouts, but that organization found it too difficult to maintain and returned it to her.

A New Vision

Christine’s parents had been significant arts patrons in New York City, and she carried that standard forward throughout her life. In 1972, through a friend, she met musicians Luca and Arlene Di Cecco, members of the Rowe Quartet at Duke University. They were young, energetic, and vibrant, and the three developed an immediate rapport.

Thus, the idea for turning Garth Newel into a home for chamber music performance and education was born. Garth Newel Music Center was officially inaugurated in 1973, 51 years after the Kendalls built the estate.

A Lasting Legacy

The property had been languishing, with deferred maintenance increasing through the years. So the Di Ceccos, in addition to teaching students and planning and performing concerts, had to address many issues as they restored buildings and managed the property. It’s a never-ending process that continues to this day.

Many would have given up at some point, with so many challenges, but the Di Ceccos persevered. They transformed the concert hall and established a respected music tradition. Because there were limited options for dining after concerts at that time, Arlene created delicious post-concert dinners that became legendary.

Christine bequeathed the property to Garth Newel Music Center Foundation in 1981 along with a modest endowment. In 1994, the Doubleday Facility was added to the back of Herter Hall to provide much-needed administrative space along with a commercial kitchen where the culinary team can prepare the gourmet meals available to concert-goers to this day.

Acknowledgement: Much of the information in this article is drawn from “Honoring the Past,” an article by Lee Elliott and Michael Wildasin that was published in GNMC’s 50th Anniversary Program Book. I am indebted to them for their excellent research.